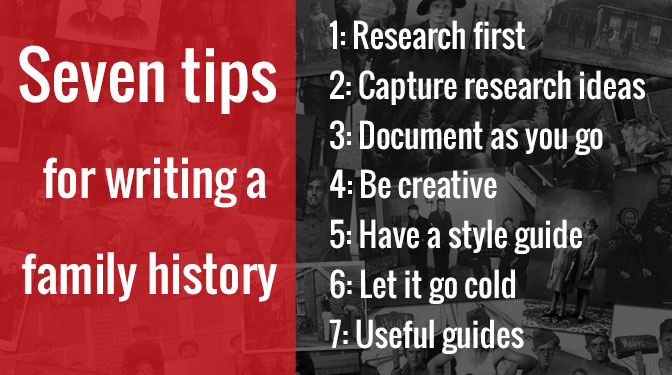

Writing a family history is more than exporting a report from your genealogy program. A family history has hand-crafted sentences that describe the lives of your ancestors. I have written several of these stories, including a Kinship Determination Project for my portfolio for the Board for Certification of Genealogists. Here are seven practical tips for writing such a narrative.

1: Research first

Before you start writing, make sure you have finished most of the research. For each person in your narrative, including parents, siblings and children, you want to know when and where they were born, married and died. You want to know their occupations and where they lived.

For the main characters in your story, you want to research their lives in a wide range of sources, not limited to vital records. You will want to do research in land records, court records, police records, town records and whatever other sources might be appropriate for that time and place.

You will also want to study literature that will help you to understand the time and place they were living in, to learn about:

- size and history of the towns

- economic circumstances

- wars and conflicts in the area

- diseases and disasters

- means of travel for migrating ancestors

- occupations and the work that these people did

- laws and regulations that may have affected their lives and choices

2: Capture research ideas for later

There will always be more sources to consult. At some point, you just have to sit down and write what you have. You may find out that you have more than you knew.

You may discover gaps in the story and things you want to research. Although tempting, I try to not go off to do more research the minute I discover a gap. Instead, I will create a research report, and put these questions in the “suggestions for further research” to capture these ideas. I will then finish writing the section I was working on before evaluating whether I really need to do that research.

You can also capture these research questions in the “To do” list of your genealogy program or in a program like Evernote or Trello; whatever works for you. The important thing is to capture the ideas without getting side-tracked from your writing.

I will try to put off doing the actual research until I’ve written up the whole story about that person or even the whole family. This allows me to prioritize all the research that needs to be done and to combine several research items in the same trip to a repository.

3: Document & cite as you go

Document your research as you go. You can do this in the form of research reports to yourself and by entering the information in your genealogy program (I do both).

Create source citations while you have the source in front of you. While writing the story, add citations for every fact that is not common knowledge. Don’t wait for the second draft, but add the citations the moment you use a source for your story so you won’t have to go back to look for it later. (I learned this one the hard way. At one point, my Kinship Determination Project had 500 footnotes that read “To Do.” Do as I say, not as I do!)

I have a simple rule of thumb to determine if something is common knowledge: If a fact is important enough to have its own lemma in Wikipedia, I won’t cite it. That does not mean that my audience will necessarily know about this event, but they can look it up. For example, if I write a blog post that mentions the Eighty Years’ War in the Netherlands, I will not cite any sources for the fact that it lasted from 1568 to 1648 even though I realize that most readers are from outside the Netherlands and won’t know these dates. I trust they will recognize this as a historical event and will know how to find out more if they want to.

I use the highlighting function of Word to mark citations that I am unhappy with, for example because I’m not satisfied with the formatting or because I think I need a better-quality source. I use the following color-coding:

- Green: citations that are done

- Yellow: citations that need some additional formatting or checking

- Red: citations that need serious work, e.g. a “to do” citation

- Purple: citations to sources that I would like to replace with higher-quality sources, e.g. an index that I would like to replace by the actual document. This will also go in my “suggestions for future research” section in my research plan.

Using color coding allows me to see at a glance which citations need work.

One of the nice features of Word is that you can convert Footnotes to Endnotes (on the “References” tab, click the little arrow button next to “Footnotes” in the section). This is useful as you get close to finishing since it allows you to see all the notes in one big list. If you use color coding, you will instantly notice any that need work. Before you finish, you will want to replace any subsequent citations to the same source with short citations. You may want to create a backup copy before you do this, in case you later want to recycle pieces of your writing in another context. At the very last, you can replace any citations to the same source as the previous note with “ibid.”

Once you’re done reducing the notes, you can change the endnotes back to footnotes. Footnotes make it easy for your readers to see the sources for your information since they are on the same page, and they will be included in any copies of the page.

4: Be creative in how you tell the story

When you start writing, you will have a whole pile of sources to work with. Especially with the data of our genealogy programs in front of us, it can be tempting to just put all of the sources in chronological order and to discuss them one at the time. This can make for a pretty boring read.

Add some of your own style. Perhaps the chronological order is not the best way to tell their story. Are there any themes you would like to discuss? For example, you could have a section about the houses where they lived, or about their religious beliefs. It might make sense to put all the information you have about those topics together rather then switching between topics just because something else happened first.

A family history is about the people you are writing about. It is not a travelogue of your genealogical research. Think about it this way: your readers want the hole in the wall, without hearing about how you purchased the drill 🙂

I personally prefer not to talk about the sources in the narrative. The narrative focuses on the people and everything they did. If it is necessary to discuss a particularity of a source, I do that in the footnotes. By focusing my main text on the people, it will be more pleasant for people to read, especially for readers who are not that into genealogy.

Everyone will have their own preferred way of writing. I like to emerge myself in the research of the person, then write a section about a topic while only occasionally looking at the sources, so I don’t copy literally but use my own words that fit into a larger story. I will then go back to all the sources and add or correct details, add some quotes that will help to bring the story alive and to add the source citations. Other people may first want to create an outline of the whole story and then fill that in as they go.

5: Have your own style guide

Good writing benefits from consistency. Along the way, you will have to make several choices about handling certain situations. For the basics, you can rely on style guides like the Chicago Manual of Style (for technical aspects of writing), Evidence Explained (for citations) and Numbering your Genealogy (for numbering systems), but these will leave room for your own style. Documenting these choices in your own style guide will make sure that these choices are consistent.

Here are three examples from my own style guide:

- When referring to events, first mention the place, then the date. E.g.: “Jan de Vries was born in Apeldoorn on 15 March 1822.”

- Write dates as day Month year, without abbreviating the name of the month, e.g. 15 March 1822.

- On the first occurrence of a place, cite province and country (Leeuwarden, Friesland, Netherlands). On subsequent occurrences, only cite the place unless it can cause confusion.

6: Let it go cold

Ideally, you want to have someone to proofread the text for you. But even then, you will want to re-read your own work. By putting the writing in a virtual drawer for a few days or even weeks, you will be able to look at it with fresh eyes and will notice things that you won’t otherwise. Printing it and reading from paper will also help you to see it in a different light. Or change the font or color of the paper, to trick your brain into seeing it differently.

When proofreading, don’t just focus on the details like grammar and spelling. Make sure you think about the big picture: does the story “flow”? Are there any topics that are missing? Are the different parts of the story well-balanced or is one aspect given too much or too little attention?

7: Useful guides

Here are four books that have been helpful to me:

- Henry B. Hoff and Penelope Stratton, Guide to Genealogical writing (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2014).

I found this guide to be very helpful with the process of writing a genealogical narrative. It contains many tips on formatting and styling. It can be purchased from the American Ancestors website. - Elizabeth Shown Mills, Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace, 3rd edition (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2015). This book is essential in learning how to cite sources. Available from Amazon

.

- Joan F. Curran, Madilyn Coen Crane, and John H. Wray, Numbering Your Genealogy : Basic Systems, Complex Families, and International Kin, rev. ed. (Arlington, Va.: National Genealogical Society, 2008). This book explains the intricacies of the various numbering systems. Following one of these establish systems help your readers to know who is who. Available from the National Genealogical Society.

- Chicago Manual of Style, 16th edition (Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2010). This guide will help you with the technical aspects of writing, such as when to use a comma, where to place quotation marks, and how to handle foreign-language quotations. Available from Amazon.

More tips?

What are your favorite tips for writing a family history? Please share them in the comments.

Great tips! One more addition: indeed, create context! Personally, I wouldn’t limit this to “what happened in the city”, but add images of this ancestor / the places they worked at and an autograph of the person in question. I realise this isn’t always possible, yet if you have the chance it really makes the person come to life.

Excellent suggestion, thanks!

Yvette,

I want to let you know that your blog post is listed in today’s Fab Finds post at http://janasgenealogyandfamilyhistory.blogspot.com/2016/04/follow-friday-fab-finds-for-april-1-2016.html

Have a great weekend!

Thank you Jana!

This is a wonderful guideline and very timely as I am just starting an “official” book on my ancestors and want it to include more than just dates & places.

Good, clear advice!

This is well written guidance – clear and concise, and I’m sure it will be very helpful to me when I start putting it all together! Thank you very much Yvette. I’ve been putting this most important (and fun!) bit off for a long time.

A really interisting blog with so many tips and tricks the colour codeing must be the best tip ever, many thanks. Mike

I like to encourage my fellow family historians to be clear, consistent, concise and compelling and hopefully their work will stand the test of time. Julie

I am thinking about embarking on my own journey of genealogical writing. I am hoping to start w/ my grandparents and write about them, my dad and his siblings and spouses, my sister, brother, and cousins and all of our kids. I want to do this before there is another generation added. This means I have to get going because the oldest great-grandkids are 23, 21 and 21. Do you have any tips for writing something like this? I am thinking about color coding, but am unsure about how to do it so it makes sense.

I was thinking dad would be red, his siblings would be orange, green, blue and purple. After this generation, I have to decide if me, my sis and bro would be next as red then also include all of our kids, or should I go basically in chronological order, just putting the right colors on the pages for each descendant? So Dad, Me, (my kids), Sis (her kids), Bro (his kids), then Uncle, cousin (his kids), cousin (her kids)…. etc OR

Dad (red), Uncle (orange), Aunt(green), Uncle(blue), Uncle (purple) then Me (red), Cousin(orange), Sis (red), Cousin (orange), Bro(red), Cousin(green), cousin (green), cousin (blue), Cousin (blue), cousin(purple) THEN the next generation which would be the great-grandkids… Red, red, red, blue, blue, red, red, blue, green, blue…. etc

Not sure if that is clear, but it is helping me to write it out, even if you never comment.

Thanks!

jody

I would recommend using a standard genealogy numbering system to show each person’s place in the tree. Numbering your Genealogy is a great help to explain how to use the numbers (available through NGS. You can complement the numbering system by using colors for different branches, but I would not rely on color alone. Your publication may be used by people who are colorblind or people may make photocopies in black-and-white.

This is a great help. I have gathered a lot of information on ancestry.com and want to put it together in a format that is not just a list of names, places, and dates.