Today, a new privacy law went into effect: The General Data Protection Regulation, or its Dutch implementation, the “Algemene Verordening Gegevensbescherming.” The new law requires a solid foundation for processing data of living people, especially when it concerns special personal data such as race or religion. The new law has larger fines, and requires better processes to prevent data leaks.

Genealogists already know we have to be careful when sharing information about living people. We are familiar with the limits of 100, 75, and 50 years for public records of birth, marriage, and death. And if we’re honest, it has long surprised us that we are not allowed to view a birth record from somebody born between 1918 and 1938, but could find that information without any problems in the population register.

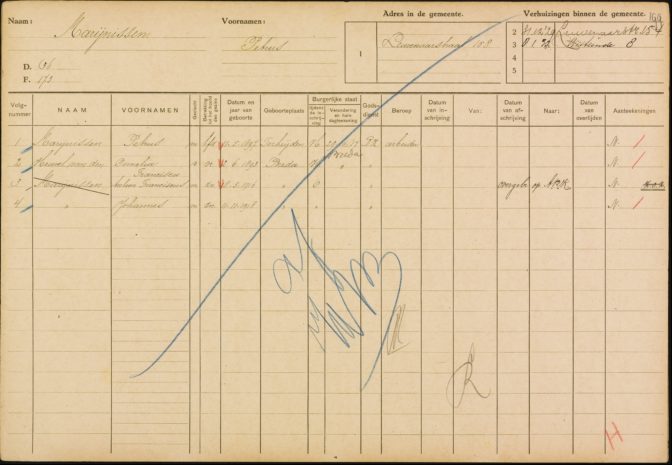

Thanks to volunteer projects like Vele Handen [Many Hands], many population registers are made available online; allowing us to search them by name on the websites of the archives or via Google. Several municipalities received complaints from people who found their own personal information that way. As a result, the Association of Dutch Archives issued a recommendation to take all the family cards from the period 1920-1940 offline. Many archives have already taken the information down.

I want to plead for a more nuanced approach. Thanks to the wonderful indexes, we know who are mentioned on the cards. Some of the cards only contain people who were born more than hundred years ago, where there are no privacy issues. An algorithm can easily determine which cards contain recent information, and only take those offline. The archives could also choose to keep the index entries online for people born more than hundred years ago, so we can see the index entries even if the card itself is taken offline because it also contains information about people who were born later. Redacting relgion, which usually is the only protected personal information on a family card, could be another alternative to deleting the whole scans.

An even better solution would be if archives could use the “Basisregistratie Personen” [Basic Person Registration], the current and automated version of the population register, to check if a person is already dead. An anual export from the Basic Person Registration containing only deceased people would suffice.

There are several technical solutions to limit the privacy protection to living people, so that the family cards will remain available for researchers. But just in case they’re taken offline, I’ve downloaded all the family cards that mention my ancestors.