Many archival collections in the Netherlands have been cataloged in finding aids according to the principles of the nineteenth-century archivists Feith, Fruin, and Muller. Their Handleiding voor het ordenen en beschrijven van archieven [Manual for orderning and describing of archives] from 1898 states that a finding aid should merely provide an overview of the records, but should not discuss their contents. A finding aid should not make consulting the records unnecessary.

A finding aid describes who created the archive, such as an organization or a noble family. Persons that appear in the records are rarely named. If it was useful to describe these persons, this was handled in a separate supplemental finding aid, for example as an index on persons or a card catalog.

In the paper world, that distinction makes sense—the finding aid should not become too big to print. But online, the distinction feels artificial. Knowing the content is essential to efficiently search the records.

Many of the classical finding aids and supplemental finding aids have been digitized and put online. The supplemental finding aids have been turned into searchable databases and indexes. The finding aids themselves often ended up in a different part of the website. Sometimes, an online finding aid indicates what population registers have been preserved of a municipality, but they don’t mention that a complete index of the persons in these records can be found elsewhere on the site.

Thankfully, these different presentations are converging. The digital finding aid often links to the corresponding index, and the indexes often refer to the description of the record in the finding aid, including the option to view the record online, have it scanned, or reserve it for consultation in the reading room.

Many of the records are unindexed, however. The massive digitization efforts yield tons of scans, but only a portion of those are indexed. In many cases, the generic description in the classical finding aid is the only information we have about the content of the site. That description does not include the names of the persons or places users search for. How can we make sure that researchers find the scans of the topics they are interested in?

I expect that this will lead to interesting experiments in the years to come. Tests with automatic character recognition of manuscripts combined with Named Entity Recognition technology that can detect names in texts. New viewers to see the scans, that help you to easily navigate scanned bundles of paper. Virtual assistants that suggest records to consult from a website or genealogy program.

Archives can find guidance for these changes in one article from the Archivist 2.0 Manifesto: “I will let go of existing practices if there is a better way to do things, even if these practices once seemed so right.” Because contrary to what Feith and consorts felt, physically visiting an archive is quickly becoming unnecessary.

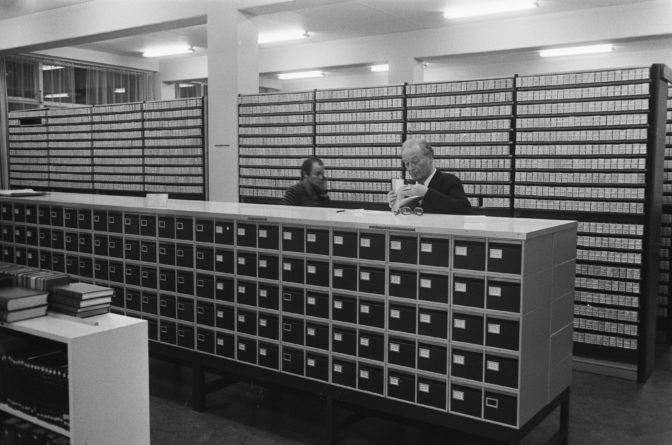

Reading room of the Amsterdam City Archives, 1973. Collection Nationaal Archief (public domain)

A Dutch version of this column first appeared in the July 2017 issue of Gen, the quarterly magazine of the Central Bureau for Genealogy.