You see it everywhere online: fake news. Sensational stories, written to draw attention and gain clicks for ads. Fake news about the presidential candidates may even have influenced the US elections.

Even in genealogy, it is often the less reliable information that draws our attention. Complete family trees can be found online, but may not be based on solid research. Indexes are easier to access than original records, but may have mistakes. And because of copyright restrictions, genealogy publications from a hundred years ago are more easily available than recent articles with the latest insights.

No matter if we’re dealing with fake news or with genealogy, we need to analyze the quality of our sources to find out the truth. In general, an original source is more reliable than an index, that may have copy or interpretation errors. A well-documented authored work, such as a family tree with complete source citations, is more reliable than a work that does not cite its sources.

Understanding the bias of the sender can help us to spot unreliable sources, then and now. For example, in 1697 my ancestor produced a charter from 1580 that gave him the right to a fixed rent. Exactly what he needed to win a civil suit against his landlord. It became suspicious when his neighbors produced similar records, from different years but in the same handwriting. Just like the owners of the fake news websites today, they had a financial interest in the information they were spreading. The charters turned out to be false. A good lesson that we need to look for ulterior motives even when dealing with original records that are hundreds of years old.

Ironically, my American genealogy software allows me to enter “alternative facts.” These do not have any political implations, but serve to record variations in the data. For example, I can enter alternative names, to document all the name changes of my Achterhoek ancestors who named themselves after the farm they lived on.

I can also record conflicting information as “alternative facts.” When different sources give different birth dates for a person, I can enter these as alternative dates, citing the source for each fact. That facilitates recognizing and resolving conflicts.

By comparing the different dates and the quality of the underlying sources, I can often draw a conclusion about the most probable birth date or the approxmiate period when it must have taken place. I choose to enter that as the preferred date, and mark the alternative dates as hidden. That allows me to access the information, but ensures my online tree does not become “fake news.”

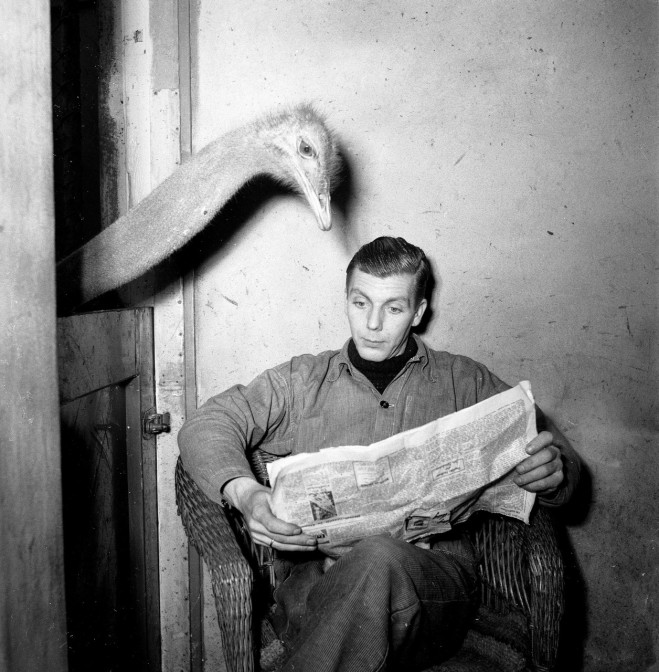

Ostrich reading newspaper. Credits: Nationaal Archief (CC-BY)