A horige is a serf or villain, an un-free farmer who was bound to the land. Serfdom started in the Middle Ages. In most parts of the Netherlands, it was abolished by the 1500s. In some parts, like the eastern parts of Drenthe, Overijssel and Gelderland, a diluted form of serfdom continued until the French occupation of 1795.

Rights and duties of serfs

The specific rights and duties of a serf depended on the overlord, time and place, but in general, serfs have the following features in common:

- The status was hereditary. Usually, all children of a woman who was a serf were serfs too. If a free woman married a serf, the overlord of the man often demanded that she became a serf too before he gave permission. In exchange, one of their children would be let free.

- The right to the farm was hereditary, passing on from father to son (or to a daughter or other relative). A serf could not be removed from the farm unless he failed in his duties.

- When a farm transferred to another serf, usually after the death of the former farmer, the new serf had to pay a tribute.

- When a serf died, the overlord received a part of his inheritance, the heriot. Depending on the time and place and the standing of the serf at the time of his death, this ranged from everything that the serf owned to half the four-legged cattle.

- Most serfs paid a relative rent, usually a share of the harvest. By the 17th century, these rents were converted to monetary (fixed) rents. There were often other scotage duties, such as working part of their time on the lord’s demesne, delivering wood for the lord’s fires, chopping ice in the lord’s moat, providing food and drink for the lord and his party when they were hunting, et cetera.

- Most serfs were only allowed to marry serfs of the same overlord. If they married outside their circle, they had to get permission first and pay a fee, or face paying a fine or even loss of the right to the farm.

- Serfs could buy their freedom, but the cost was usually prohibitive. This would deprive them of their right to take over the farm. In some cases serfs were only allowed to buy their freedom if they found another person to take their place.

- Serfs were sometimes exchanged between overlords, for example if they wanted to marry someone from the other lord. In earlier times, say before 1650, serfs could be bought and sold.

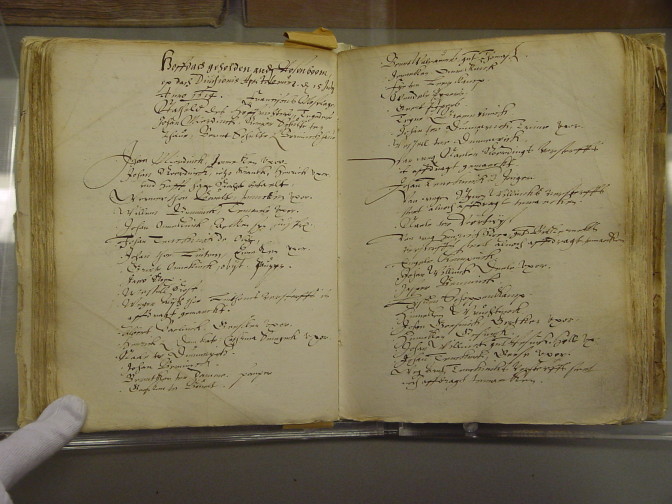

- Most overlords kept a registration of their serfs and require them to attend (often annual) meetings to record changes to their situation.

Former serf farm and shed in Winterswijk (Kossink). Credits: IJ.Th. Heins, Rijksdienst voor Cultureel Erfgoed (CC-BY-SA)

Example: Serfs in Winterswijk and Aalten

Many of my own ancestors in Winterswijk and Aalten were serfs. The serf records of one of the overlords in that area, the Lord of Bredevoort, go back to 1506 and include amazing genealogical information, such as lists with names of all the serfs in a given year, disputes over the right to take over a farm and contracts for serfs being traded between overlords who owned serfs in the same neighborhood if a serf wanted to marry someone who belonged to a different lord.

Source

- Manorial court of Miste, Bredevoort, serf register 1598-1688, call number 013C, unnumbered pages, meeting of 15 July 1614; Nassause Domeinen, Record Group 0357; Gelders Archief, Arnhem. These records have been transferred to the Erfgoedcentrum Achterhoek en Liemers since photographing them.

Great information about how serfdom functioned in the Netherlands. Is there an English translation of the Serf book(s) of Miste? Unfortunately I can not read the names and I am sure I had people in Aalten/Winterswijk that were on that list.

I am still confused on how/when/why my ancestor Jan Vossers became Jan Hof te Ijzer at IJzerlo around/before 1668. Did he buy the farm? (and I don’t mean the slang term of ‘buying the farm’ meaning he died….. 🙂