I had been doing genealogy for over twenty years when I started taking paying clients. I had done pro bono work for friends, researching all over the Netherlands, but that was more in a coaching capacity and often did not require formal reporting. In the years since I started taking clients, my skills have grown. Here are five ways in which being a professional genealogist has made me a better researcher.

1: Nothing beats prose writing

When you work for a client, one of the things that you need to do is write a report. That report not only contains your conclusions, but also describes your process. You explain which sources you looked at, analyze the sources for clues and describe what else you need to look at and why. You compare information from different sources to each other, noting similarities that strengthen your case or discrepancies that may indicate you’re on the wrong path, or that need to be resolved.

Writing things down like that forces you to slow down and take note of every detail. It triggers processes in the brain that don’t happen when you just add facts to your family tree software.

For my own research, I now write reports to myself, which I rarely used to do. It is amazing to see how often the information you need to prove parentage is already there, if you analyze the sources properly. In other cases, writing down may not solve the problem immediately, but will generate new ideas for future research.

An example of this is my analysis of a population register, where I suddenly realized that the order of the information on the record could only mean that a man was living with the mother of an illegitimate child before that child was born, making him a good candidate to be the child’s father.

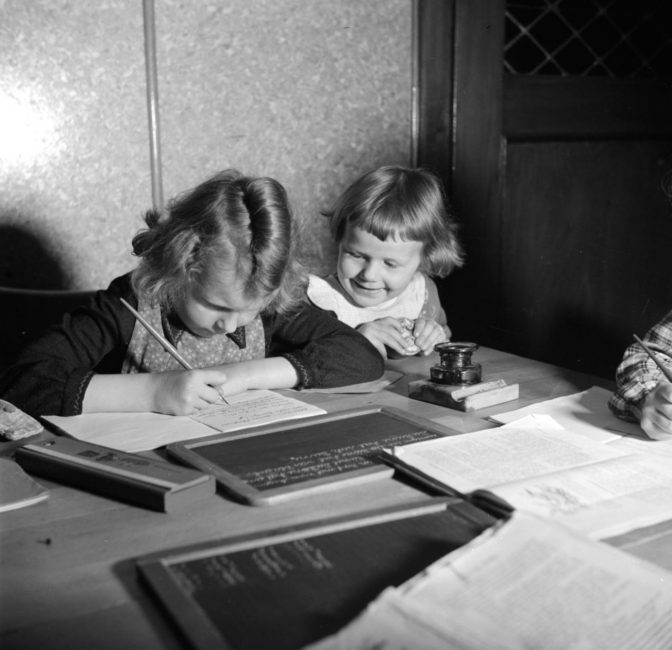

Credits: Willem van de Poll, collection Nationaal Archief (CC-BY)

2: Exposure to new problems helps you grow

When you are only working on your own family, your research experience is probably limited to certain locations, ethnicities and types of sources. Unknowingly, you may have developed tunnel vision.

Every client problem will throw you in the deep end. You will be working with a new family, possibly in a place where you haven’t done any research, using sources that may not be available for your own family. You will need to learn how to find out what records are available for that time and place. You will learn how to analyze the information that the client gave you, to determine if it is a solid starting point to base research on. You will learn how to assess the reliability of sources and spot weaknesses.

3: Focused research

Being on a client’s clock means you can’t spend countless hours chasing after long shots. You learn how to determine which research strategy is the most likely to give you a good outcome. You will learn how to plan efficient research, by prioritizing research in sources that offer the best chance of providing relevant evidence.

You will also learn to work with a focused research question, so you are sure you are researching what the client wants to know, instead of wandering off. A focused research question will guide your research and help you to think about sources to consult.

4: Learning about new strategies

When I decided I wanted to become a professional genealogist, I ramped up my education. I had already been a member of various local genealogical societies and read their magazines, but I now set out to find better examples of quality research. I became a member of the Koninklijk Nederlandsch Genootschap voor Geslacht- en Wapenkunde [Royal Dutch Society for Genealogy and Heraldry], that publishes a journal with high-quality articles. I also joined several organizations in the United States, including the National Genealogical Society, New York Genealogical and Biographical Society and New England Historic Genealogical Society and read their journals.

The NGSQ especially provides excellent case studies that focus on methods and strategies to solve complex genealogical problems, often involving indirect, negative or conflicting evidence. It does not matter that you don’t descend from these families, or that your ancestors lived elsewhere; many of these articles will teach you how to build complex proof arguments to prove who the parents were even in the absence of direct evidence.

Another way I educated myself is by purchasing recordings of lectures given at the National Genealogical Society and Federation of Genealogical Societies conferences. I listen to them in the car on my way to the archives, with the client problem running in the back of my mind, and often find inspiration to try out a new research strategy.

Credits: Jac de Nijs, collection Nationaal Archief (CC-BY)

5: Applying standards

As I worked on becoming certified by the Board for Certification of Genealogists, I studied the genealogical standards that they formulated. They overlapped with the best practices I had developed for myself and I saw how incorporating these standards in my own work would make me a better genealogist. I applied these standards in my client projects and personal projects, and they are now my normal way of doing research.

I had always been hesitant to call a theory proven if I did not find any direct evidence. We have so many reliable sources in the Netherlands that provide direct evidence of parent-child relationships that I always felt “lazy” for considering something proven if I had not found direct evidence. Of course, not all cases can be solved by direct evidence, even in the Netherlands. And direct evidence can be wrong.

The Genealogical Proof Standard gave me a framework to decide when I had done enough research and gathered enough evidence to build a case that can be considered proven. This has allowed me to solve many brick walls, including several of my own.

Conclusion

Getting out of our comfort zone and taking a professional approach to genealogy improves our skills. You don’t need to take clients to achieve these benefits. You can educate yourself, you can immerse yourself in other problems, and you can start writing reports for your own brick walls. You will be amazed at how much better you will get.

Enjoyed reading this article. I have always envied the wonderful Dutch records and came to believe that Dutch genealogy was far easier than US genealogy with its lack of records. But I soon learned that there are brick walls in my Dutch families as well. Reading your thoughts help me identify resources and continue to inspire me (to keep banging my head against these brick walls). And for the record, all of my Dutch families are documented much further back than nearly all my families, except for one Mayflower family (which we all know also includes Dutch roots/records).

One thing I loved about client research was exploring different records!! What I hated was writing reports!! And a difficult thing was sticking with the clock and NOT following some of those tempting side trails.