When you are working with old manuscripts, it is tempting to think they are original records—the first recorded version of the document. However, even old manuscripts may be derivative records—copies, transcriptions, or abstract of older versions. Sometimes, the original record does not survive and the derivative is all we have to work with. But we have to keep in mind that it may have copy or interpretation errors.

In the past, when people created a copy, they may not necessarily have tried to make an accurate transcript; their goal was to capture the truth. If they thought there was a mistake in the original, they may have silently corrected it; perhaps accidentally introducing a mistake or including information that was not known at the time the original record was created.

Here are some examples of derivative sources I have used in my project to prove my descent from Eleanor of Aquitaine:

- The marriage supplements of Dorothea Smulders from 1835, which included an extract of her baptismal record from 1809 (generation 6).

- Register of annuities of Tilburg from 1532 that included an entry for an annuity from 1391 (generation 20).

- A 1434 charter that includes the text of a 1357 charter (generation 20).

- A 15th century manuscript of the Brabantsche Yeesten, a copy of a chronicle about Brabant originally written in the early 1300s (generation 23).

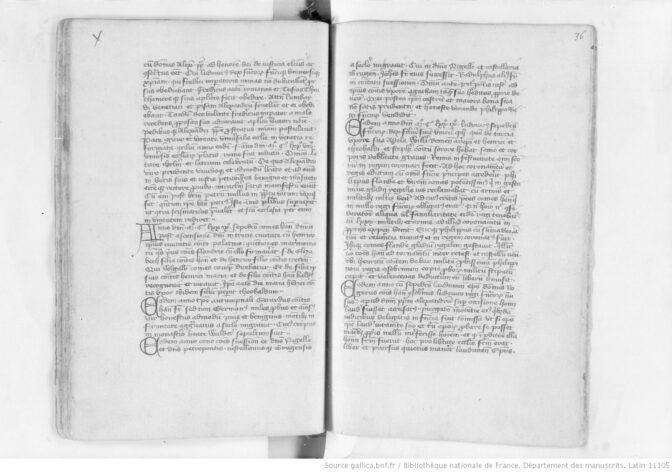

- A 15th century manuscript of the Annals of Hainaut, originally written around 1200 AD (generation 26).

Annals of Hainaut. National Library of France, Latin 11105.

Bishop’s Transcripts in England are a good example of something old not being original…of course, if the parish register is gone, then we use the BTs as our best alternative, and hope to find other corroborating evidence.

And even the originals aren’t always correct – human error is a constant!

Good observations. For several of the examples in this post, the originals do not survive either. We use the best quality evidence we can, and sometimes that means using a derivative. It’s good to be aware of the risk of copy errors though.