I recently came across a publication that abstracted Dutch records. In the publication, the compiler had grouped a marriage record and two baptismal records together. The parents of the child in the first baptismal record, a year after the marriage, had the same names as the married couple. The name of the child in the second baptismal record matched the bride’s, and that child was baptized 22 years before the marriage.

By the way he grouped the records, the compiler of the abstracts implied all these three records belonged to the same family: a married couple, the baptism of their son, and the baptism of the wife. Subsequent users of this publication took this as fact, and cited his publication.

However, the original publication gave no explanation why the compiler thought the bride was the same woman as the child in the baptismal record 22 years earlier. The name was the same, but that was it. Subsequent research showed she was in fact born elsewhere, in a different country even, and this was not her baptism.

Abstracts can be a great intermediate step in research since they can help us to efficiently identify the records that are most likely to help us answer our research questions. But the next step should always be to check the original records. The original record may have more information, and they may reveal interpretations and assumptions by the compiler of the abstract that turn out not to be based on evidence.

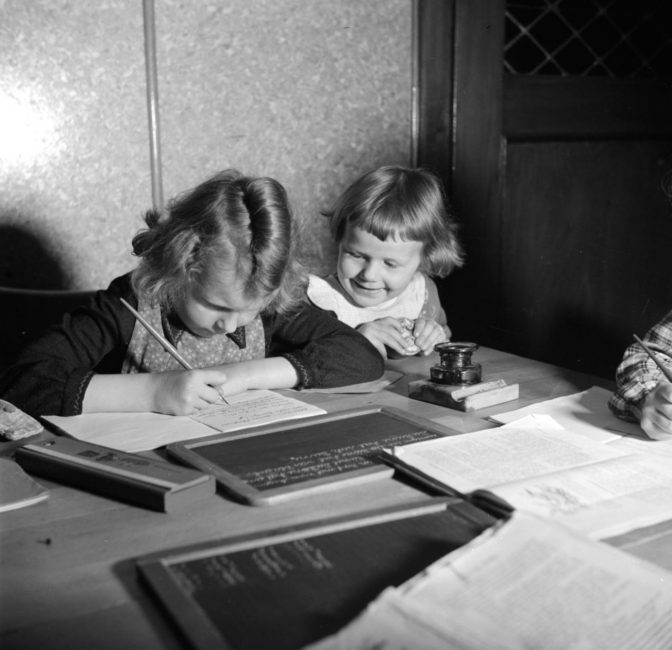

Credits: Willem van de Poll, collection Nationaal Archief (CC-BY)