A forty-four-year-old man lies buried in Winterswijk, the Netherlands. His grave has an ordinary marker, but with an unusual design: it has a toy on it. People who walk past it wonder why a grown man would have a toy depicted on his grave. They don’t know that the man who rests there was my uncle, Dinant, who had severe mental disabilities.

Grave of Dinant Hoitink (photo: Yvette Hoitink)

During his birth, Dinant was deprived of oxygen. He suffered severe brain damage, resulting in mental disabilities. His condition got worse as he got older because of frequent epilepsy attacks that caused further damage to his brain. He never learned to talk and could only do robotic tasks like feeding himself or walking next to somebody. And he could play with his favorite toy, carefully putting the blocks through the holes and then taking them out again. Day in, day out.

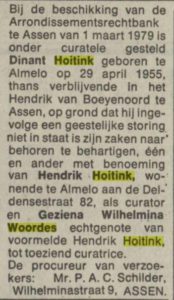

Appointment of my grandparents as guardians of Dinant. Nieuwsblad van het Noorden, 27 March 1979, p. 20, col. 3; Delpher.

Dinant makes me wonder how many other relatives like him I had. People with severe disabilities leave few records. They would have been incompetent to enter into any contracts, and unable to get married. Few if any had children.

Throughout most of our history, people with severe mental disabilities would not have had a legal guardian unless there was a need for a legal representative, for example if they were entitled to an inheritance. A guardianship appointment may be one of the few indications of their disabilities that we can find today. Another type of record I have come across is a contract between family members, where one of them agreed to take care of a mentally disabled sibling for the rest of his life in exchange for the sibling’s share in the inheritance. In one sad case, I found a notarial contract where a father leased his disabled son to a traveling circus to be put on display.

In the twentieth century, it became common for people with disabilities to have guardians or curators to handle their affairs. My grandparents Henk Hoitink and Mien Woordes were appointed as curators of Dinant on 1 March 1979, as I found in the newspaper.

At the time of Dinant’s death in 2000, I was in the process of becoming a co-curator of Dinant, since my grandparents were getting on in years and wanted to make sure Dinant would be taken care of after they were gone. Dinant passed away before the legal side was finalized.

My grandfather only survived Dinant for a few months, while my grandmother went on to live for another nine years. That was the first time in sixty years that she did not have to take care of a child. Dinant had been living in an institution specialized in taking care of severely disabled persons, but visiting him and making sure he had everything he needed had been a major part of my grandparents’ lives.

If we find siblings or cousins in our trees who remained unmarried, we do not usually ask ourselves why. Were they not marriage-minded, or were they unable to get married because of a disability? Or were they perhaps not allowed to marry the person they loved, because that person had the “wrong” faith or gender?

People like Dinant did not have children. No descendants will delve into their lives and put them in their pedigree charts. But they were part of our families. Taking care of a sibling or a child with disabilities would have had a major impact on our ancestors’ lives, like it did for my grandparents. By going beyond the vital records, and searching for court or notarial records, we can sometimes find out about these relatives and understand an aspect of our family history that usually remains hidden.

Dinant Hoitink (1955-2000)

onroerend om te lezen.

Yvette, this is a really important topic and I’m glad that you’ve made this contribution for the genealogy community. You raise good points that we should consider in our research.

Have you come across censuses for the Netherlands that logged disability? The 1880 US census did this, albeit with some pretty harsh terms (by today’s standards). I’m wondering if this may be another source that could help with the research.

Yvette, this was so beautifully written. Thank you for introducing us to Dinant.

Yvette,

Dinant seems to have had his charming side, to judge by his smile and his curls. Thank you for bringing his story into the open, and for your family’s care of him.

I had a first cousin with Down Syndrome. When he was born, in 1949, the doctors told his parents he would never function–walk, talk, feed himself, etc. They were advised to put him in an institution. They refused, and raised him with their other two sons. He went to what Americans call “special education” schools, to learn at his own pace. I remember him as funny, and a part of the extended family. I do know he required more care than the other two. His mother created a group home where as a young adult he lived with half a dozen other disabled young adults, with supervision. The neighbors didn’t want them around, until they got used to them. Eventually he had his own apartment in a building rented by the state for disabled adults, again with supervision and help, but with more independence. He was found a job putting together pizza boxes, which he held for many years, going to and from on the public buses. Eventually he got Alzheimer’s Disease, which he died of at age 65. Now that people with Down Syndrome live longer, it’s known that there’s a genetic connection between the two conditions.

What I don’t know is whether there are public records which would document his condition, or whether he will simply remain a fond family memory.

Doris

This is beautifully written — thank you!

Thank you, that is wonderful to hear.

Very sweet post.