As you get further back in time, you will get to the point where you find the first person who adopted a surname. Sometimes that’s a distinct event; for example when a Frisian family adopts a last name in 1811 because it is required by the Napoleonic laws upon the introduction of the civil registration.

Before 1811, there were no laws and regulations that mandated people to have surnames. Names were often adopted gradually. Not all family members may have adopted the name. A person may appear with the last name in one record, and only by patronymic or another name in another record.

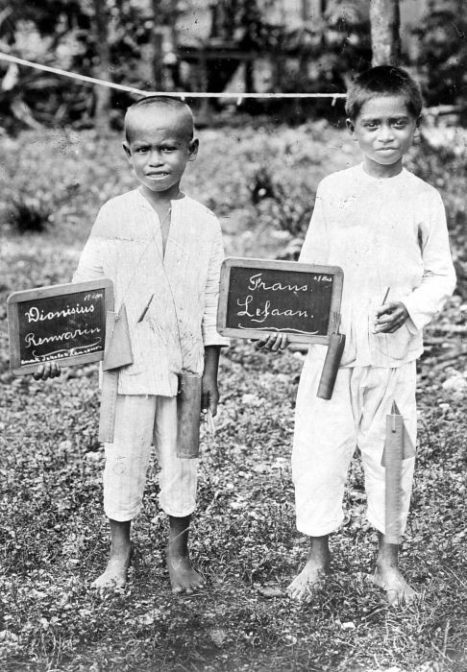

Two boys show their new Christian names. Credits: Tropenmuseum via Open Cultuurdata (CC-BY-SA)

A person may even appear with 2 or 3 different surnames, and brothers can have different surnames.

I find that to be so in my paternal line.

“Sometimes that’s a distinct event; for example when a Frisian family adopts a last name in 1811 because it is required by the Napoleonic laws upon the introduction of the civil registration.”

Not quite. For some reason, the Frisian provincial surname registration, starting in 1811, seems to be rather persistent in pushing people to come forward to register a name, apparently more so than in other provinces. For many Frisians it may have been necessary to do so in the true absence of a surname. However, I find plenty of examples of families coming forward who already had a surname, which, for all intents and purposes could be as old as two or more centuries, going back to the sixteenth century. The consideration that they may not have been using the surname in practice could be a reason to push for registration in Friesland, but then the municipality of Hillegersberg in the province of (South-) Holland should have been pushing hard for registration too. In Hillegersberg it was not very common to carry surnames well into the eighteenth century, although most people had them. I see the same in the countryside of Groningen province. When the surname was there, although not carried, in most places a simple adoption of the name was all that was necessary. The only group of citizens for which registration of surnames was a must throughout the country were the (Ashkenazim) Jews, who on the whole went by patronymics, without (hidden) surname.

I would be interested to know if the provincial and municipal authorities in different parts of the country had different policies in this respect, and what the rules and local considerations were to push for registration.

“Two boys show their new Christian names. ”

Perhaps not the best illustration for this blog post. The label “new Christian names” is misleading, because technically that only refers to the first (baptismal?) names. There is nothing “Christian” about Dutch surnames. What is happening in the picture is an example of cultural imperialism disguised as a civilising mission, robbing these boys of their original names and identity, bringing them into the fold of Dutch colonial “civilisation”. There is no comparison of any sort with the registration of surnames in Dutch society as a cultural phenomenon or under Napoleonic law as a legal phenomenon.