This is the twenty-third post in a series about my possible line of descent from Eleanor of Aquitaine. In the first post, I explained how I discovered the possible line, and how I am going to verify it one generation at a time. In the last post, I proved that my eighteenth great-grandmother Lijsbeth van Mieren was the daughter of Jan van Wijfliet, Lord of Blaasveld.

Jan van Wijfliet, son of Duke John II of Brabant

The previous phase uncovered a rent for 116 pounds given to Jan van Wijfliet in 1349 and to Jan Back in 1356. Jan Back was the husband Lijsbeth van Mieren and Jan van Wijfliet’s son-in-law. The previous phase also showed that Jan van Wijfliet was the lord of Blaasveld by virtue of his wife, Margareta van Pipenpoij.

These and other records will be analyzed for evidence about the identity of Jan van Wijfliet’s parents. It’s a long read, so if you prefer you can skip to the conclusion to read the summary.

Note about names:

From this point forward (backward?), the ancestors are known historical figures, whose names are routinely translated in English literature. The English names will be used when discussing the ancestors, except when quoting from original records.

Bastard son of John II Duke of Brabant

In his book Trophées tant sacrées que profanes du Duché de Brabant, Christopher Butkens listed several bastards of John II Duke of Brabant, including Jan van Wijtvliet. Butkens gives a short biography.

Jan van Wijtvliet was a knight and lord of Blaesvelde. He purchased the city of Grave from John lord of Cuijk and was then called Lord of Cuijk and Blaesvelde. He was in conflict with John of Cuijck over payment who attacked Grave. Jan van Wijtvliet of was killed during the siege. Jan van Wijtvliet was married to Margarete Pipenpoy daughter of Rudolph Pipenpoy, knight and lord of Blaesvelde, and marshal of Brabant, from whom he inherited the manor of Blaesvelde.1

Butkens’ book was published in 1724—four centuries after Jan van Wijtvliet’s life. It refers to original records, but cannot be trusted outright and should be verified using original records during Jan van Wijfliet’s lifetime.

Son of Elzebeen van Wijfliet

Only one known contemporary source directly identifies a parent of Jan van Wijfliet. On 30 June 1347, Jhan van Wijfliet lord of Blaersvelt received half of a tithe in Babyloniënbroek, of which he gave the proceeds to his mother, lady Elzebeen deaconess of Gherechem, during her lifetime.2

Earlier researchers and transcribers identified “Gherechem” as Gorinchem, a town in Holland.3 However, no evidence was found of a convent there with a lady Elzebeen as its deaconess.

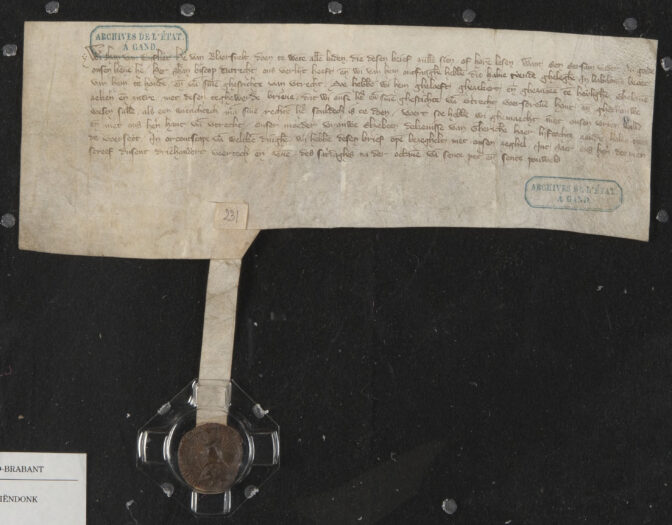

On 2 October 1347, a notary in Den Bosch acted as executor of the estate of knight Wilhelm de Buscho and on behalf of Elze de Wijflijt, deaconess in Gerresheim, when he established a rent of five pounds for Sophia van Wijflit, that would revert to the canonesses of Gerresheim after her death.4

This record, found in the records of the convent of Gerresheim near Düsseldorf in modern-day Germany, shows that an Elze de Wijfliet was deaconess in the convent of Gerresheim three months after Jan van Wijfliet gave his mother Elzebeen, deaconess of Gherechem the proceeds of the tithes. Elze and Elzebeen are variations of the same name. The combination of the correct role, the variation of the same first name, and the surname that matches Jan’s own surname proves that this is the same person. The interpretation of “Gorinchem” was incorrect and should be “Gerresheim.”

Windmill in Berlicum

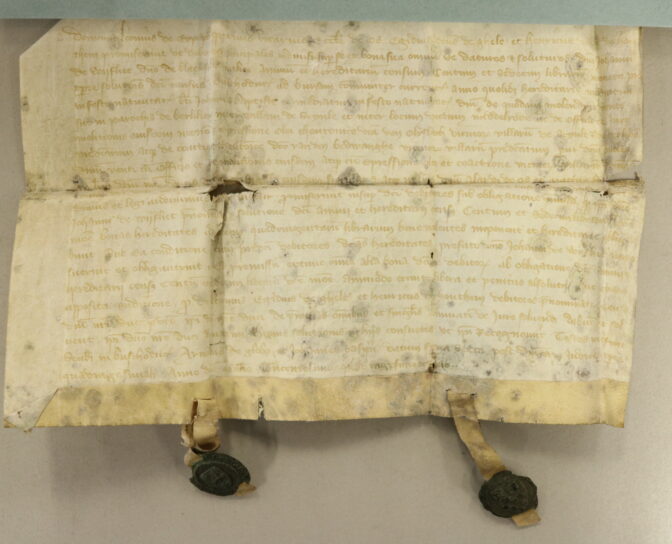

On 31 March 1349, Jan van Wijfliet, Lord of Blaersveld, knight, received a rent of 116 pounds of the windmill in Berlicum. The original charter survives.5

On 2 August 1356, this rent was assigned to Johannes Back, son of the late Aert called Berthout Bac van Tilburg, steward of the Duke of Brabant.6 The previous blog post identified him as the husband of Jan van Wijfliet’s illegitimate daughter Lijsbet van Mieren.

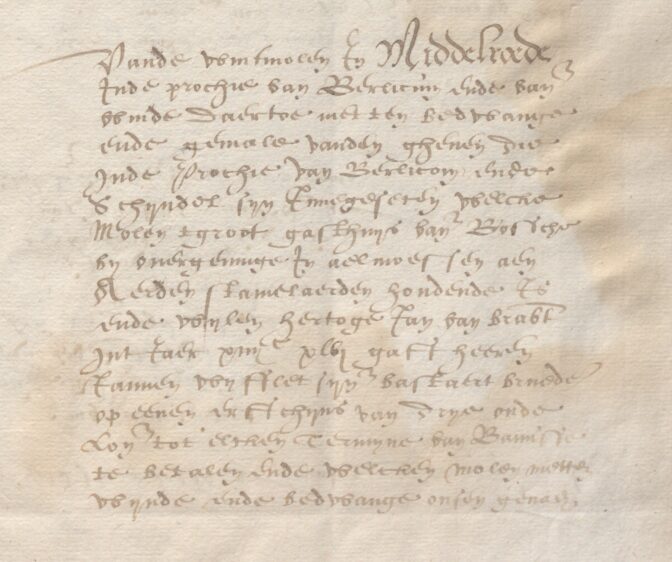

Steward’s accounts from 1574-1575 mention a rent of three pounds from the wind mill in Middelrode in Berlicum. The description of the rent includes its provenance, as copied from earlier (no longer existing) records. It says that the late Duke Jan van Brabant [John of Brabant] gave the rent to lord Jan van Wijfflet his bastard brother in the year xiiiic xlvi.7

That date in roman numerals translates to 1446. This must have been a mistake, since there was no Duke John of Brabant in the year 1446. Most likely, a copy error was made, introducing an extra ‘i’ for the century, and this transfer was done in 1346. The detail of Duke John of Brabant giving it to his bastard brother Jan van Wijfliet is less likely to have been introduced as the result of a copy error than an extra i, so that information is more reliable.

This rent was drawn from the proceeds of the same mill as in the 1349 charter, that gave Jan van Wijfliet, Lord of Wijfliet a rent of 116 pounds. This combination makes it clear that the bastard brother Jan van Wijfliet of duke John of Brabant in 1346 was the same person as Jan van Wijfliet, lord of Blaasveld in the 1349 charter. In 1346, the duke of Brabant was John III, son of duke John II of Brabant. John III was Duke of Brabant from 1312 until his death in 1355.8

Brother of John III Duke of Brabant

Other records confirm the relationship between Jan van Wijfliet, lord of Blaasveld, and John III, Duke of Brabant.

John III Duke of Brabant called Jan, lord of Blaersvelt, his brother in a request to Pope Clemens VI in 1343. He asked the pope’s permission to give Jan an altar for his prayers. The request was part of a series of requests by John III Duke of Brabant relating to church donations and benefices.9

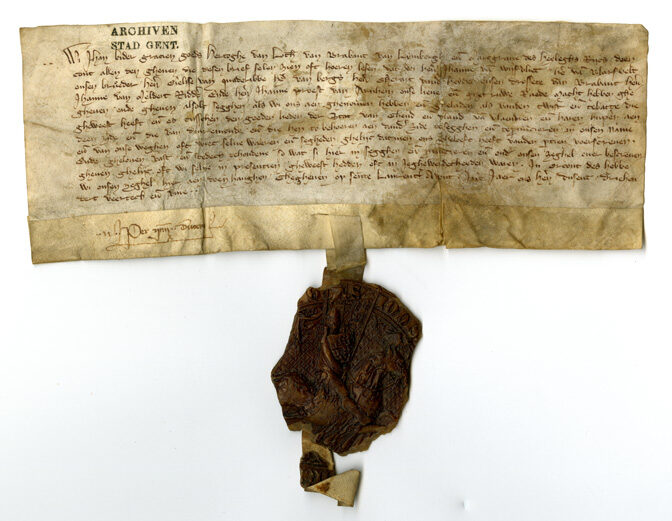

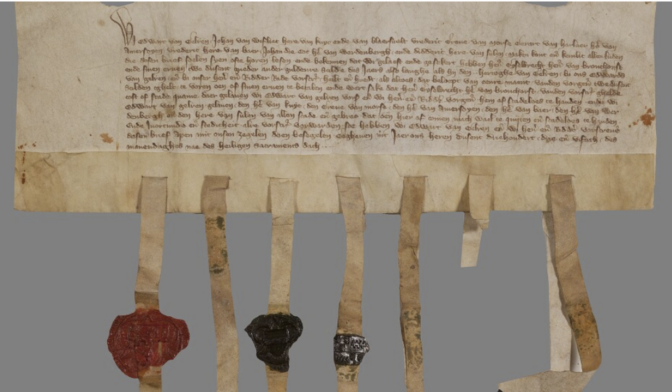

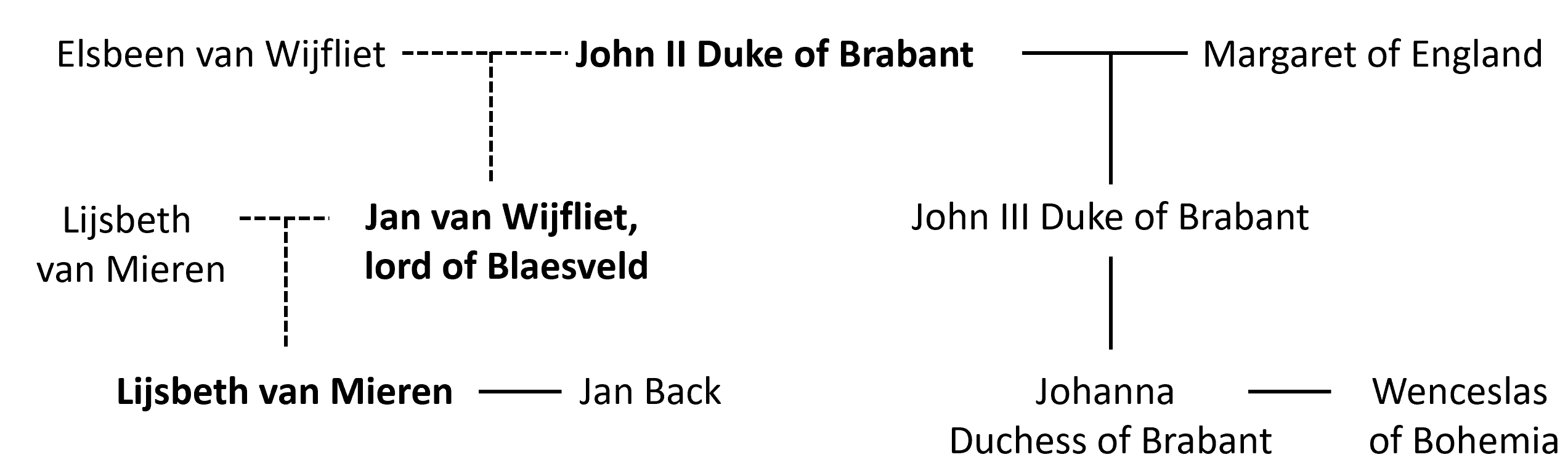

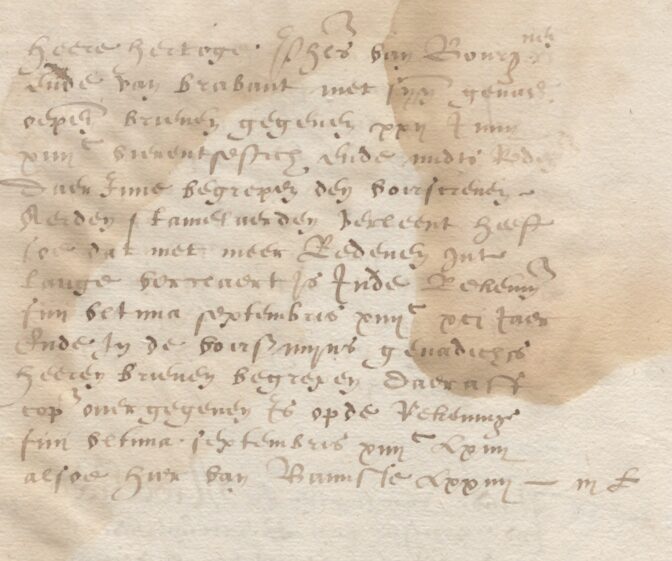

In a charter of 9 August 1345, John, Duke of Lothier, Brabant and Limburg, gave power of attorney to his brother John, lord of Wijfvliet and Blaesfelt, to end the differences between the cities of Ghent and Termonde [Dendermonde].10 The charter explicitly refers to Lord John as “onsen brueder” [our brother].

9 August 1345 charter

Two days later, John, Duke of Lothier, Brabant, and Limburg proclaimed an agreement between the cities of Flanders and Termonde, in his role of arbiter of their dispute. The proclamation was made in the presence of the council of the duke, including Jan van Wijfvliet, lord of Blarsvelt.11 This charter does not identify a family relationship between the duke and Jan van Wijfvliet, but a place on the council would be fitting for a brother, even one born out of wedlock.

11 August 1345 charter

Councillor to John III Duke of Brabant

Jan van Wijfliet sealed and witnessed several charters of John III Duke of Brabant, and acted on behalf of the duke on several occasions. In his book Brabant tijdens de regering van Hertog Jan III [Brabant during the reign of Duke John III], Piet Avonds described Jan van Wijtvliet as one of the most influential members of the council of John III Duke of Brabant.12

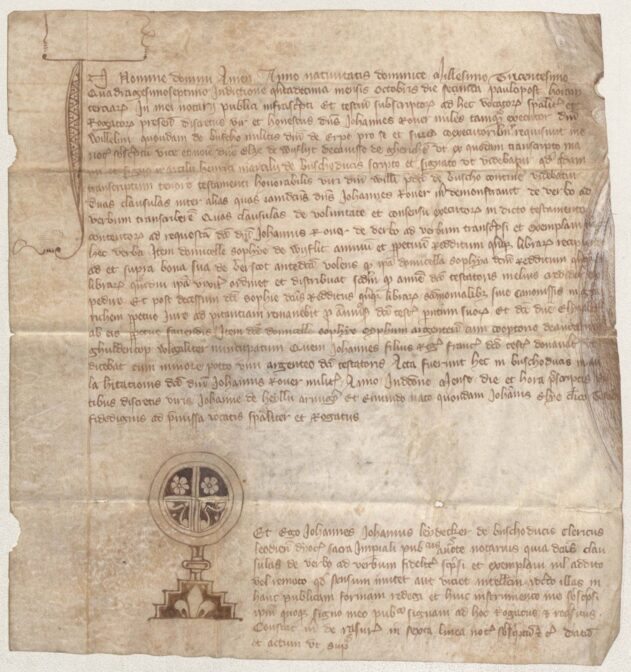

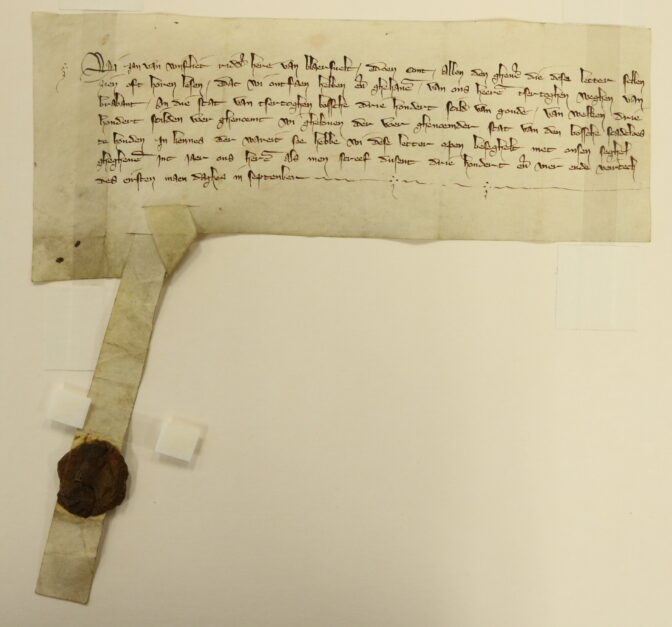

In September 1344, Jan van Wijfliet received 300 guilders from the city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch on behalf of the Duke of Brabant.13

Seal of Jan van Wijfliet on the 1344 charter

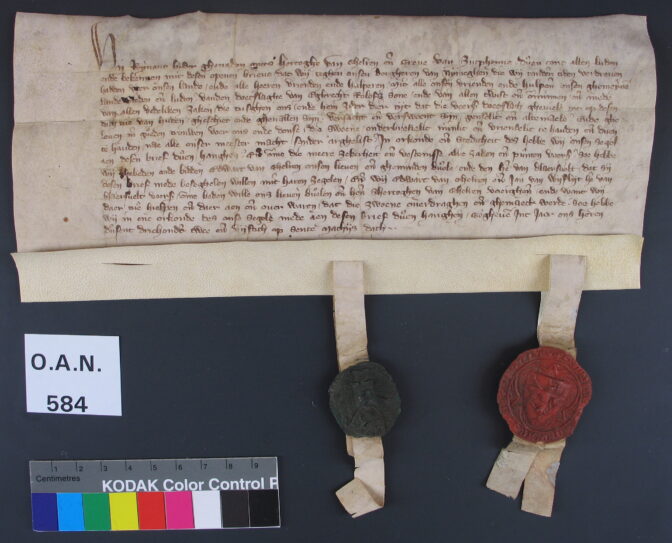

John III of Brabant’s daughter Maria married count Reinald III of Gelre on 1 July 1347. After the marriage, Jan van Wijtvliet was appointed as steward of Gelre to support the young duke and gain influence in Gelre.14 In that capacity, he sealed a charter of reconciliation between Reinald of Gelre and the citizens of Nijmegen in 1352.15 The seal matches that of the 1344 charter.

These interactions show that Jan van Wijtvliet was a trusted councilor to John III Duke of Brabant, consistent with him being his half-brother.

John III, son of John II

John III of Brabant’s parents were John II, Duke of Brabant and Margaret, daughter of King Edward I of England. The 14th-century chronicle Brabantsche Yeesten describes how John II Duke of Brabant was succeeded after his death by the third John, whom he’d procreated with Margaret of England.16 Contemporary sources confirm this relationship. The prenuptial agreement between John II Duke of Brabant and Margaret of England was made on 22 January 1279.17

The 1347 charter told us that Jan van Wijfliet’s mother was Elisabeth van Wijfliet, not Margaret of England. For him to be the bastard brother of John III Duke of Brabant, he must have been the son of John II Duke of Brabant.

John II Duke of Brabant died in 1312.18 Jan van Wijfliet first appeared in records in the 1330s, suggesting he had just reached adulthood by then. He must have been a child or even unborn at the time of John II of Brabant’s death. This explains why no contemporary records have been found where John II of Brabant mentioned Jan van Wijfliet as his son, even though John III mentions him as a brother.

Uncle of Duchess Johanna of Brabant

In 1360, Wenceslas of Bohemia, Duke of Luxembourg, Lothier, Brabant, and Limburg, and his wife Johanna inherited a mill in Weerde from their uncle John Wijtvliet, lord of Blaasveld. The record survives in the form of a copy in the chartulary of the Duchy of Brabant. In the record, Wenceslas and Johanna refer to “onsen lieven oom oom heer Janne Wijfliet” [our dear uncle lord John Wijfliet].19

Johanna, wife of Wenceslas of Bohemia was the daughter of John III of Brabant.20 The mention of Jan van Wijtvliet as her uncle in the 1360 record is consistent with the 1343 request to the pope and 1345 charter that named Jan van Wijfliet as the brother of John III Duke of Brabant [her father].

Lord of Cuijk

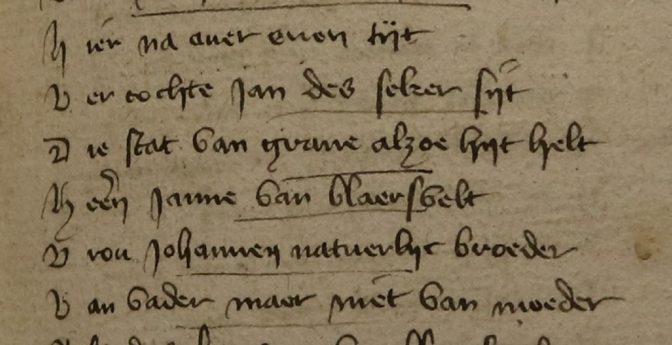

The Brabantsche Yeesten chronicle has a section about the sale of Grave by John of Cuijk to Jan van Blaasfelt, that mentions him as the brother of Lady Johanna:

Hier na aver enen tijt,

Vercochte Jan, des seker sijt

Die stat van Grave, alsze hijt helt

Heren Janne van Blaersvelt,

Vrou Johannen natuerlijc broeder,

Van vader maer niet van moeder.21

Translation:

Afterward, after some time,

John [of Cuijk] sold, which is certain,

The city of Grave

to lord Jan van Blaesvelt

Lady Johanna’s natural brother,

by father, but not by mother.

“Lady Johanna” in this period was Johanna, Duchess of Brabant, the daughter of Duke John III of Brabant, mentioned in the 1360 charter above. By calling Jan van Blaesvelt her natural brother, this chronicle implies that Jan van Blaesveld was the illegitimate son of John III, not John II, as stated in the 1345 and 1360 records.

The Brabantsche Yeesten chronicle was started by Jan van Boendale in the early 1300s. Other writers continued the chronicle after Van Boendale’s death. The manuscript that has the section about Jan van Blaesveld was written by Wein van Cotthem.

In her thesis Middeleeuws Kladwerk: De Autograaf van de Brabantsche Yeesten, Boek VI (Vijftiende Eeuw) (Medieval Draft: The Autograph of the Brabant Gests, Book VI (Fifteenth Century), Astrid Houthuys analyzed the manuscript. She recognized that this manuscript was a draft, which Van Cotthem corrected over time. Analysis of the watermarks in the paper showed the manuscript was started around 1432. Houthuys identified several corrections and additions during the creation of the manuscript. Van Cotthem showed himself to be a serious historiographer, who valued historical accuracy over a convenient rhyme.22

This means that Van Cotthem must have thought the information that Jan van Blaesveld was Johanna of Brabant’s half-brother was correct, or he would not have written it this way despite the nice broeder-moeder [brother-mother] rhyme. However, he wrote this a century after the events, and his sources had other errors that needed correcting. This makes the chronicle less reliable than the charters from 1345 and 1360, and the papal request in 1343, that were created by John III of Brabant and Johanna, who had personal knowledge of their relationship to Jan van Wijfliet, lord of Blaasveld.

A charter from 1353 confirms that Jan van Wijfliet was the lord of Cuijk. In the charter, Johan van Wijfliet, lord of Kuyc and Blaersvelt, was one of the noblemen who promised Gyselbrecht, Lord of Bronckhorst the sum of 2,000 old shields per year as long as he kept faith with the Duke of Gelre.23

1353 charter

The following year, Jan lord of Kuyc and Blaersvelt, and lord Giesbrecht van Hoeps, knight, came to an agreement to end their dispute about their rights and tithes.24

These charters confirm the information in the chronicle that lord Jan van Blaesveld was also the lord of Cuijk.

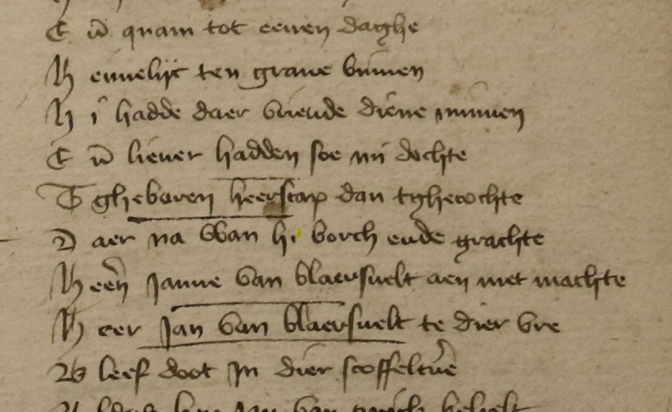

The Brabantsche Yeesten chronicle describes how Jan van Wijfliet met his end:

Her Jan van Cuyck, doe ic u cont,

Heeren, vrienden ende mage,

Ende quam tot eenen daghe

Heimelijc ten Grave binnen:

Hi hadde daer vriende, diene minnen,

Ende liever hadden, soe mi dochte,

Tgheboren heerscap dan tghecochte.

Daerna wan hi borch ende grachte

Heeren Janne van Blaesvelt aen met machte.

Heer Jan van Blaesvelt, te dier ure,

Bleef doot in dier scoffeltuere.25

Translation:

Translation:

Lord John of Cuyck, I inform you,

Lords, Friends, and Kinsmen,

one day secretly came into Grave

He had friends there, who loved him

And preferred the born lord to a purchased one

After he gained the fortress and the moat,

He attacked Lord John of Blaesvelt with all his might

At which time Jan van Blaesvelt

Remained dead in the altercation.

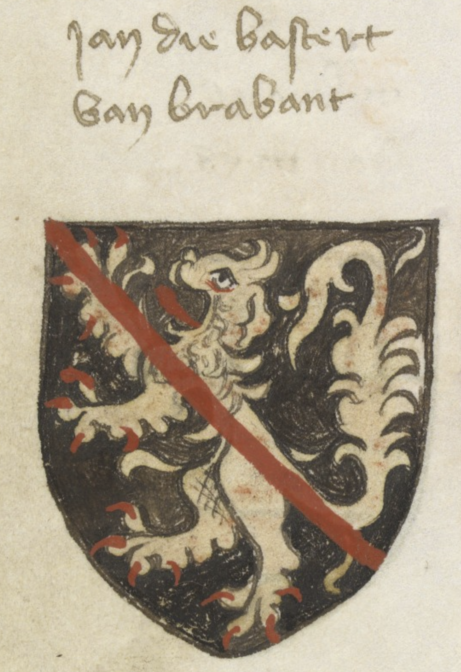

Coat of arms

Illegitimate children were not allowed to use their father’s coat of arms. Acknowledged noble bastards would often adopt the father’s coat of arms but with a change. In most cases, this was a bar or beam diagonally across the shield.26

Jan van Wijfliet’s seal showed a climbing lion facing left, with a bar diagonally across it.27

Seal of Jan van Wijfliet on the 1344 charter

The Dukes of Brabant used a gold lion on a black shield as their coat of arms, as can be seen from this manuscript showing the coats of arms of various noble families from 1405.28

That manuscript showed the same coat of arms with a bar across it being used by Jan [John], bastard of Brabant.29

This coat of arms matches that used by Jan van Wijfliet, lord of Blaesveld in the 1344 charter. The coat of arms used by Jan van Wijfliet shows the lion of Brabant, plus the bastard cross bar, consistent with him being the illegitimate son of a Duke of Brabant.

Conclusion

Several pieces of evidence prove that Jan van Wijfliet lord of Blaesveld was the illegitimate son of John II Duke of Brabant.

A charter from 1347 identifies Jan van Wijfliet’s mother as Elsbeen van Wijfliet, deaconess of the Gerresheim convent. Jan van Wijfliet’s connection to the Dukes of Brabant must have been through his father.

John III Duke of Brabant named Jan van Wijfliet as his brother in a 1343 request to pope Clemens VI and in a 1345 charter. Jan van Wijfliet was the duke’s trusted council member and acted on his behalf on several occasions, consistent with being his half-brother. A record from 1574/5 showed that Jan van Wijfliet received a rent in a mill from his brother Duke John of Brabant in 1446, an apparent mistake for 1346. Jan van Wijfliet, lord of Blaesveld owned that mill in 1349.

Johanna Duchess of Brabant, daughter of John III, named Jan Wijfliet her dear uncle in 1360. A later chronicle that named Jan van Wijfliet as Johanna’s brother from another mother was not based on eye witness testimony and must have been mistaken in the nature of their family relationship.

John III was the son of John II Duke of Brabant, who died when Jan van Wijfliet was a child or even unborn. That explains the lack of contemporary records that mention Jan van Wijfliet as the son of John II Duke of Brabant.

The Dukes of Brabant used a gold lion on a black shield as their coat of arms. Jan van Wijfliet lord of Blaesveld used the same shield with a bar, indicating his status as a bastard.

Apart from the conflicts resolved above, all evidence agrees that Jan van Wijfliet was the illegitimate son of John II, Duke of Brabant, and Elsbeen van Wijfliet, who later became deaconess of the Gerresheim convent.

That’s twenty-two generations down, six to go!

Next up: Generation 23 – John II of Brabant

- Christopher Butkens, Trophées tant sacrées que profanes du Duché de Brabant (The Hague, Netherlands: Chretien van Lom, 1724), book IV, p. 369-370; consulted as digital images, Google Books (https://books.google.nl/books?id=b0hDAAAAcAAJ : accessed 28 September 2019).

- Jan van Wijfliet, charter about tithe in Babyloniënbroek (30 June 1347); call no. 169a, Convents of Marienkroon and Mariendonk in Heusden, Record Group 239; Brabants Historisch Informatie Centrum, Den Bosch; finding aid and images, Archieven.nl (http://www.archieven.nl : accessed 26 December 2017).

- See for example Brabants Historisch Informatie Centrum, “Samenvattingen van oude akten” [abstracts of old records], database, Archieven.nl (http://www.archieven.nl) which includes an abstract for this charter that identifies the mother as Lady Elzebeen, deaconess of Gorinchem.

- Johannes Leydecker to Sophya de Wijflit, annual interest (2 October 1347); charter no. 68, Monastery of Gerresheim, Urkunden [Charters] AA 0277; Landesarchiv NRW, department Rheinland, Duisburg, Germany; scans provided by Landesarchiv.

- Leonis van Erp et al to Johannes van Wijfliet, charter (31 March 1349); call no. 261, Reformed Citizens’ Orphanage ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Record Group 0212; Erfgoed ‘s-Hertogenbosch, ‘s-Hertogenbosch.

- Aldermen of ‘s Hertogenbosch, vidimus of charters of 1349 and 1356 (25 July 1434); call no. 260, record group 0212, Erfgoed ‘s-Hertogenbosch.

- Brabant Domains, account by Cornelis Cleerhage, steward, 1574-1575, fol. 10, rent from Berlicum mill; call no. 87, Domains, council and steward-general, Record Group 9; Brabants Historisch Informatie Centrum, Den Bosch; finding aid and images, Archieven.nl (http://www.archieven.nl : accessed 18 August 2019).

- The reigns of the Dukes of Brabant are well-documented. See for example Raymond van Uytven, Geschiedenis van Brabant: Van Hertogdom tot Heden (Zwolle: Waanders, 2004).

- Ursmer Berlière, editor and compiler, Suppliques de Clément VI (1342-1352), p. 105, abstract 465; digitized at Internet Archive (https://archive.org/stream/suppliquesdecl01cath#page/104/ : accessed 18 November 2019). Attempts to consult the original at the Vatican Secret Archives or obtain a scan were unsuccessful, so a published abstract was used instead.

- John Duke of Brabant to Jan van Wijfliet, charter with power of attorney (9 August 1345); call no. 405, collection of charters and records of the City of Ghent; National Archives of Belgium, location Ghent; scans provided by Ghent archives.

- John Duke of Brabant, charter with proclamation (11 August 1345); call no. 407, collection of charters and records of the City of Ghent; National Archives of Belgium, location Ghent; scans provided by Ghent archives.

- P. Avonds, Brabant tijdens de regering van Hertog Jan III (1312-1356): Land en Instellingen (Brussel: Paleis der Academieën, 1991), p. 105, 109, 238.

- Jan van Wijfliet to ‘s-Hertogenbosch, quitclaim, charter (1344); call no. 2979, City Administration of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, record group 001; Erfgoed ’s-Hertogenbosch, ‘s-Hertogenbosch.

- Avonds, Brabant tijdens de regering van Hertog Jan III, p. 120.

- Reynald of Gelre to Nijmegen, charter (25 February 1352); call no. 584, City Administration Nijmegen, Regionaal Archief Nijmegen, Nijmegen; consulted as “Regesten Oud Archief Nijmegen 1166-1811,” abstracts and images, Regionaal Archief Nijmegen (https://studiezaal.nijmegen.nl/detail.php?id=16415769 : accessed 12 August 2018), abstract 65.

- “Brabantsche Yeesten,” consolidated edition, Digitale Bibliotheek Nederlandse Letteren (https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/boen001brab01_01/ : accessed 12 September 2019), book 5. The original manuscripts of the chronicles survive in fragments and parts in different libraries and collections. This edition uses the surviving manuscripts to reconstruct the original text.

- Edward, King of England, prenuptial agreement for his daughter Margaret to John Duke of Lorraine and Brabant, charter (22 January 1279); call no. 101, Account Chamber, charters and chartularies of the Duchy of Brabant, Limburg, and Over-Meuse, Record Group I 282; National Archives of Belgium, Brussels. Also, John Duke of Brabant, bride gift to his son’s future wife Margaret daughter of Edward King of England, charter, undated [March 1279]; call no. 102, RG I282, National Archives of Belgium. The original charters were consulted and photographed, but permission was not received to publish them.

- Geschiedenis van Brabant.

- Duchy of Brabant, chartulary XXII, fol. 510v, inheritance by Wenceslas of Bohemia and Johanna, his wife (1360); call no. 8, Account Chamber, charters and chartularies of the Duchy of Brabant, Limburg, and Over-Meuse, Record Group I 282; National Archives of Belgium, Brussels. The original chartulary was consulted and photographed, but permission has not been received to publish the photos.

- Geschiedenis van Brabant.

- Wein van Cotthem, “Brabantsche Yeesten,” book VI, fol. 63r; Ms. 17017, Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels. Photograph by author, published with permission.

- Astrid Houthuys, Middeleeuws Kladwerk: De autograaf van de Brabantsche yeesten, boek VI (vijftiende eeuw) (Hilversum: Verloren, 2009), 119, 227-229, 254, 255.

- Duke of Gelre, Johan van Wifliet and others, charter (27 May 1353); call no. 28b, House Bronkhorst, Record Group 0381, Gelders Archief, Arnhem; consulted as finding aid and images, Gelders Archief (https://www.geldersarchief.nl : accessed 12 November 2019).

- Jan van Kuyc and Blaersvelt and Giesbrecht van Hoeps, charter (15 March 1354); call no. 6713, House Bergh, Erfgoedcentrum Achterhoek en Liemers, Doetinchem; consulted as “Regestenlijst Huis Bergh” [Abstract list House Bergh], Erfgoedcentrum Achterhoek en Liemers (http://www.ecal.nu : accessed 12 November 2019), abstract 113, image and abstract.

- “Brabantsche Yeesten,” book VI, fol. 63r.

- J.A. de Boo, Familiewapens: Kentekens van Verwantschap [Family Coats of Arms: Signs of Kinship] (The Hague: Centraal Bureau voor Genealogie, 2008), 171.

- Jan van Wijfliet to ‘s-Hertogenbosch, quitclaim, charter (1344); call no. 2979, City Administration of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, record group 001; Erfgoed ’s-Hertogenbosch, ‘s-Hertogenbosch.

- Claes Heynenzoon, “Wapen Boeck” [book of coats of arms], manuscript, 23 June 1405, unnumbered page; digitized as “Wapenboek Beyeren (1405),” Koninklijke Bibliotheek (https://www.kb.nl/themas/middeleeuwen/wapenboek-beyeren-1405 : accessed 15 September 2019).

- “Wapen Boeck,” unnumbered page.

Brilliant analysis and a great read as well! Love seeing the medieval charters and documents!

Thanks, Scott! Not as much as I loved handling them, I can assure you 😁

Congratulations Yvette on the find of “Gherechem” = Gerresheim and not Gorinchem, which is definitely a breakthrough. This research is getting into the real heavy stuff now. I’m even more impressed than before.

What arguments did the National Archives of Belgium use to forbid you to publish your photographs?

Is that a general rule for them, or did it have to do with these particular charters?

I would imagine they would be proud if there documents would be used in a professional study.

The Belgian national archives make you sign an agreement before they let you photograph records that you won’t publish unless you pay a user fee of 50 euros per photo. That’s not specific to these charters but applies to all their records.

I do not want to pay since I don’t make any money from this blog post and feel strongly that records that are in the public domain should be able to be used for free. I have applied for an exception but have not heard back yet.

The royal library in Belgium had the same system, but their dispensation to pay the user fee came in just before the article was published so I added these photos.

Dag Yvette,

Mijn bewondering voor jouw prachtige genealogische vondsten en uitvoerige publikatie daarover !!

Met dank en hartelijke groet,

Gerard Lemmens

Briliant work Yvette!!! Now I wonder if I should continue to read and have the research spoilt before I untangle my own mystery because if the new knot you know about is located around my ggfather then my ggmother ancestors trail would still be “my ancestors” and I’ll land back on my brickwall (but of course I know I will read on!!!) , What’s your favorite charter so far?

This is it! This is where you tap into known nobility, who likely have published pedigrees! SO exciting.

Thank you! You’d think it would become easier, but in fact hardly anyone cites sources (let alone original ones) since it is all “common knowledge.” Actually finding reliable contemporary records is proving to be quite a challenge, but one I intend to meet head-on!